The Beatles, pt. 1: Anthony's Album Guide

My handy dandy profoundly subjective numerical rating scheme is decoded here. You can find pt. 2 here.

Please Please Me (1963) 9

With The Beatles (1963) 8

A Hard Day’s Night (1964) 9

Beatles For Sale (1964) 7

Help! (1965) 8

Rubber Soul (1965) 8

Revolver (1966) 8

1962-1966 (1973) 6

Past Masters, Vol. 1 (1988) 7

The Beatles were four young men from Liverpool, England who spent years consuming all the American music and speed they could to better perform as living jukeboxes for all-night dance parties at home and in Hamburg, Germany. Paul McCartney & John Lennon had collaborated as singers and songwriters since their teens, bonded by their wit, their love of records and the sudden loss of their mothers. McCartney’s classmate George Harrison soon joined them as guitarist, the serious one despite being the youngest. By the time EMI got them in a studio, they’d shed numerous less committed pals (the most notable, Stu Sutcliffe, establishing the group’s artistic conscience while his girlfriend gave them all existentialist moptops) and Pete Best, a drummer who wouldn’t get an existentialist moptop. With the paradoxical Ringo Starr (somehow the most amiable member despite his absurd stage name) now behind the kit and EMI house producer George Martin both experienced and open-minded enough to help realize the band’s growing ambitions, the Fab Four accidentally invented pop-rock simply by presenting a unified front and refusing ghettoization. Everybody sang lead. Everybody played an instrument. But with manager Brian Epstein putting them in well-tailored suits, the cuteness cloaked the audacity.

From our modern vantage, the rush-recorded Please Please Me might seem gestative due to a lack of orchestra pieces, psychedelia and mustaches. But if you look past the absence of back-masking and piccolo trumpet, the album remains revolutionary. Half the songs were originals, the vocals often Everly-style harmonies when John wasn’t shredding his voice, Paul hopping between a dewy coo and a Little Richard howl. The covers ranged from hard R&B to Tin Pan Alley, two numbers coming from the goddamn Shirelles. One was already a hit ballad, the other a B-Side leading Ringo to holler “let’s talk about boys! What a bundle of joy!" because that’s the hook, gender be damned (George adding a guitar solo because that’s another hook). No matter how sappy the lyric, how cornpone the pace, the band attacks each song with enthusiastic craft. The cover of “A Taste Of Honey” isn’t merely a slow bit of schmaltz, but four music nerds enjoying the ability to do a slow bit of schmaltz. It’s not unlike Jonathan Richman in aesthetic, and not unlike the Replacements’ “Black Diamond” in its ironic accomplishment.

Sure, side two didn’t need two examples of Paul at his mooniest (I wouldn’t miss “P.S. I Love You”), but the metaphysical solace of “There’s A Place” is a five star deep cut, highlighting the blossoming songwriters at the helm, and “Twist And Shout,” with John’s haggard, desperate marvel of a voice buttressed by his bros, is an immortal climax from a time when people weren’t sure an LP needed a climax. While the sound would be emulated and covered by self-conscious power pop acts from the Flamin’ Groovies to the Knack, Please Please Me isn’t “power pop,” so often a passive-aggressive conservative retrenchment, valorizing an era where a mod fashion sense and a nicotine addiction meant you could be shitty to women. These covers were celebrations of contemporary music, the energy infectious and inclusive, enjoyed across the social spectrum. They were owning their privilege to build something beautiful, not leaning on their privilege to hide the work’s weakness. Again, this was pop-rock.

Just four dudes covering a Shirelles' B-side, as they do.

A trilogy of rapturous singles followed, “From Me To You,” “She Loves You” and “I Want To Hold Your Hand” establishing their synthesis had become a distinct sound others would be wise to imitate, Lennon-McCartney a copyright holder now competing with Goffin-King and Leiber-Stoller. With The Beatles, coming mere months after Please Please Me, is blessedly more the same, with only modest evolutions. Lennon delivers more anguished Motown covers (Greg Dulli sang his parts in Backbeat, a movie about the Hamburg years, aptly), and Paul pulls off a ballad from The Music Man (by way of Peggy Lee) with aplomb, John & George quietly playing nylon-string guitars instead of shouting “shooby doo!” behind him. I used to think “Roll Over Beethoven” was an atypical weak John vocal, but I belatedly learned that’s George. Why?

It was about this time that America belatedly caught Beatlemania, EMI’s stateside partner Capitol Records avoiding distribution long enough that United Artists signed the group to a three-picture deal mainly for the domestic soundtrack rights. (Someone who was alive & knew about the band before the UK editions of the albums became the global standard in 1987 can write about their early US releases.) A Hard Day’s Night is half songs from the titular film and 100% originals, the band bouncing through their styles as confidently as the band sasses and smirks through the movie. “Can’t Buy Me Love” has Paul swaggering like he’s on Sun Records, while John’s title track bristles with newfound appreciation of adult domesticity, “home” meaning sex rather than house chores. What makes the album truly special is the B side, where - instead of having Ringo or George cover “Blue Suede Shoes” - the core duo show further growth. The arresting “Things We Said Today” finds McCartney meditative rather than moony, and the intensity of Lennon’s jealousy on “You Can’t Do That” might have spooked and been shelved by Motown’s Berry Gordy.

Bursting with ambition but suffering for material, Beatles For Sale shows the first glints of the arch studiocraft that would be the band’s fallback in later years, songs more notable for multitracking and novel instrumentation than anything else. “I’m A Loser,” “I’ll Follow The Sun” and “I Don’t Want To Spoil The Party” are expert displays of country-tinged heartbreak, but “Eight Days A Week” is merely cute, “Words Of Love” a recreation of Buddy Holly rather than an interpretation, and George and Ringo both get to do Carl Perkins numbers on the B. My take might seem harsh if you own a couple Todd Rundgren albums, but wait till you see my stance on 1967-1970.

Usually a desperate cry for psychiatric help isn't done in three-part harmony, but that's the Beatles for you.

Help!, the audio companion to a zany Bond homage the band couldn’t have cared less about, gets back a little of that Hard Day’s zhuzh, kicking off with an ironically jaunty title track despite Lennon’s lyric suggesting a nervous breakdown. “You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away” features flutes and maracas but isn’t about them, “Ticket To Ride” a masterpiece of trance guitar overdubs and romantic resentment. I’d love to say the B compares to Hard Day’s, what with McCartney giving it up for new love on the gorgeous “I’ve Just Seen A Face” and elegantly mourning his youth over a string quartet on “Yesterday.” But, for some absurd reason, those numbers are followed by a run through “Dizzy Miss Lizzy” so shrill and inane I’d think they were trying to see if a song could get rejected (narrator: "it wasn't"). Ringo’s Buck Owens tribute is a gas, though.

For most of my twenties, I would have said Rubber Soul was my favorite Beatles album. Workshopped for a full month, now that touring and movies were a thing of the past, it opens with the thrilling percolation of “Drive My Car,” followed by the sitar-graced modern romance of “Norwegian Wood.” Lennon’s “Nowhere Man” reaches empathetically for the depressed guy in the mirror, “The Word” funkily expanding from eros into agape, “In My Life” a startlingly mature reflection still spritely enough for a faux-harpsichord solo. Unfortunately, I now realize that most of the tracks I haven’t mentioned are unadulterated assholery. McCartney demands you “act your age” and call him back right now on the A, only to declare you invisible on the B. Meanwhile, Harrison seethes about your idiocy on the A, suggesting you might get a booty call but no promises on the B. Lennon’s “Girl” is a relatively charming plea for satisfaction, but then he has to go and threaten to kill you if you stray on the finale. If this wasn’t bad enough, McCartney says the “I lit a fire” at the end of “Norwegian Wood” wasn’t about smoking or staring into a fireplace in contemplation, as I assumed for years, but burning down a woman’s apartment for giving the narrator blue balls. I guess I should be glad they didn’t include either side of the concurrent “We Can Work It Out”/“Day Tripper” single, in which Paul piously pretends “my way or the highway” is a call for compromise, and John tries to make you think “prick teaser” without actually saying it. Seriously. Assholes.

Obviously in need of a break, the band took a multi-month vacation for the first time ever, doing copious amounts of drugs and checking out modern art. Paul McCartney’s aunt asked him why they always wrote about their blue balls (or love, she might have said love), and for that alone I think we should consider her a fifth Beatle. Her wise words were on his mind when he wrote the delightful rocker/cover letter “Paperback Writer,” paired with Lennon’s “Rain,” a zonked argument for sensory experience over metaphor, on what I consider their best UK single. (I might have to give the nod to “I Want To Hold Your Hand”/“I Saw Her Standing There” when it comes to domestic 45s.)

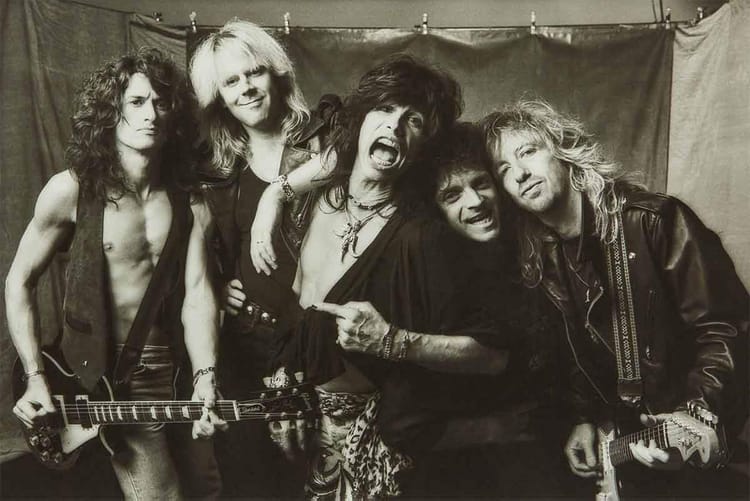

Remember that Live video where the drummer jumps around because he didn't have a kit on set? Ringo don't play that.

That single was recorded and released alongside Revolver, popularly considered the band’s best album in the ‘90s & ‘00s, when their discography (now the same on all continents) was asked to hold up to Britpop, alternative rock and sampling-based production techniques. Beck jacked the opener’s beat on Odelay, a hook so tight you might not appreciate that the Beatles dared to start an album with George bitching about taxes. “Eleanor Rigby,” Paul’s portrait of elderly solitude, thankfully keeps “Taxman” from painting John’s “I’m Only Sleeping” as a celebration of privilege instead of narcoleptic/narcotic disassociation. The sound is casually kaleidoscopic, Lennon throwing in a fuzz-guitar head trip after every pop valentine or art piece, be it Harrison paying tribute to Indian classical music or Starr pretending to be a sea captain. Alternative rocker I am, I mostly prefer the fuzz-guitar head trips, the album climaxing with “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the ur-text of every rock-techno collaboration in the late 20th century. Noel Gallagher and the Chemical Brothers aped it twice!

As I find most the band’s full-lengths in this period worth owning, I can’t find much reason to play the 1962-1966 compilation, especially when the only song included from Beatles For Sale is “Eight Days A Week." And why are there six songs from Rubber Soul, but only two from Revolver? Weird. Past Masters Vol. 1, compiling every song from 1962-1965 not on the UK full-lengths, is considerably more worthwhile, but features too many weak B-sides for me to unreservedly endorse purchase. Maybe if they left off the German-language single.

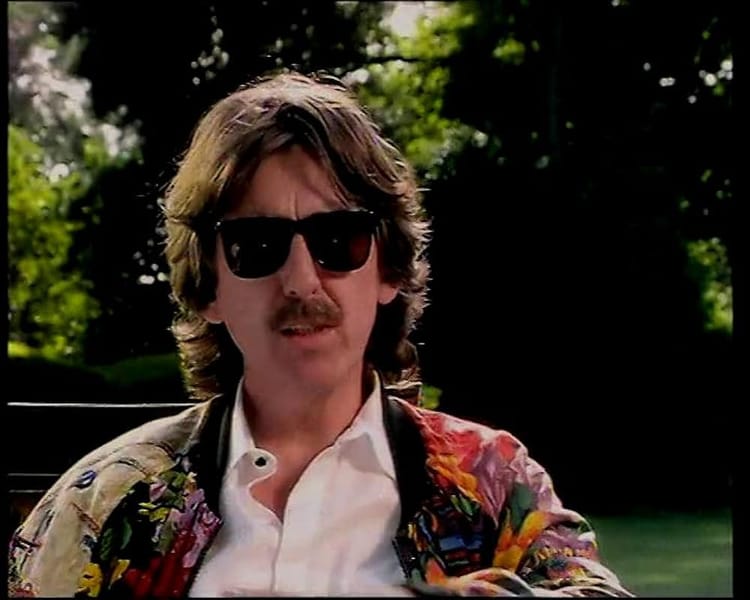

Up next: the band grows facial hair and makes the albums Rolling Stone considered their best before and after they gave the nod to Revolver.

(Please Please Me and A Hard Day's Night are respectively at 2 and 168 on My Top 300 Favorite Albums of All Time. I'm telling you this because I've found people are more inclined to discuss and share reviews if there's a quantitative element at the top or bottom they can easily debate. Prove me right!

Spoiler: as suggested by the numerical rating above, Please Please Me is making a modest drop next time I publish the list. It's still my favorite, but Paul's just too sappy on the B for me to claim perfection.)