John Prine, pt. 1: Anthony's Album Guide

Part 2 is here. My handy dandy profoundly subjective numerical rating scheme is decoded here.

John Prine (1971) 9

Diamonds In The Rough (1972) 9

Sweet Revenge (1973) 8

Common Sense (1975) 8

Prime Prine (1976) 6

Bruised Orange (1978) 5

Pink Cadillac (1979) 5

Storm Windows (1980) 8

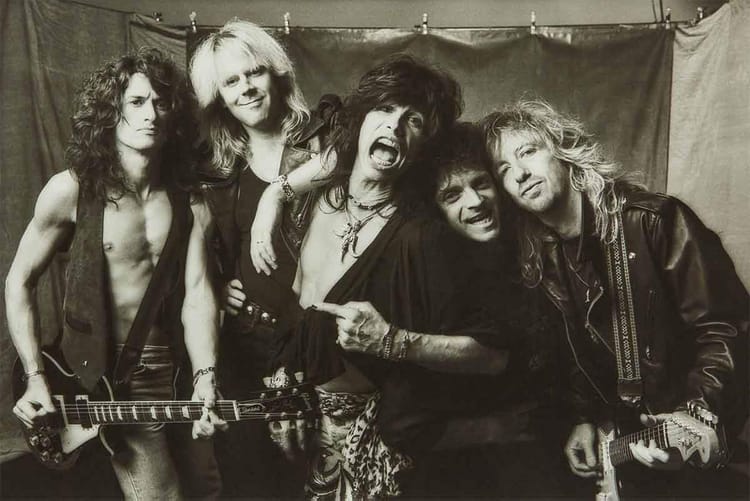

It’s no surprise that Chicago icons Steve Goodman and Roger Ebert were early champions of John Prine, a singing mailman who first approached the city’s folk scene after talking shit watching others try, and wrote prolifically because he thought you shouldn’t repeat yourself at open mic nights. His twangy voice, boyish air and acoustic set-up hid a deep knowledge and appreciation of music, the economy of country and the irreverence of rock informing his sensibility as much as folk. Ebert was the first person to write about him and Goodman was the one who made sure a touring Kris Kristofferson checked him out. Reaffirming his studly mensch status, Kristofferson wasn’t intimidated by this similarly literary/croaky upstart. The star gave him key career advice and brought him on the road, where Prine caught the eye of honchos at Atlantic Records.

John Prine, politely sharing the stage with a marijuana plant in 1972. Wasn't his idea.

Though Prine’s career is remarkably low on misses, his self-titled debut is a winner among winners, anthemic without making a fuss about it. Songs seething about the effects of war are slipped between first-person accounts of loneliness among men and women, young and old alike, everything delivered with a sardonic humor he referred to as an “illegal smile” on the opener (accidentally giving potheads an anthem as well). The song with “Jesus died for nothing, I suppose” is preceded by the one with “we lost Davy in the Korean war/ and I still don’t know what for/ don’t matter anymore,” which is preceded by the one with “eat a lot of peaches…try to find Jesus on your own,” it preceded by the one with “I’m just trying to have me some fun/ hot dog bun/ my sister’s a nun.” Smart arrangements show confidence in the material, cloaking how green the singer must have been. Moments may be too serious, silly or saccharine depending on your taste, but John Prine is an even more staggering songbook than The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, its breadth hidden by unassuming empathy. I can’t think of another singer-songwriter, male or female, country or contemporary, that would immediately undercut the self-pitying bachelor poetry of “Far From Me” with the frank housewife’s lament “Angel From Montgomery.” Ego meant far less to Prine than a good line or a good laugh.

If Diamonds In The Rough is a step down from the debut, it’s the difference between a definitive work and a great one. Rough was knocked out in less than a week, Atlantic Recording Studio in New York sounding like a West Virginia porch (albeit, a well-mic’d one). Prine’s voice is rougher and the instrumentation less considered. The bitter “Sour Grapes,” worthy of an interpretation-inviting four minutes, rushes by in just two, and frequent collaborator Goodman noted “They Ought To Name A Drink After You” is but a chorus away from standard status (Prine agreed, and still didn’t write one). “The Late John Garfield Blues” and “The Great Compromise” don’t sweat whether the titular phrase clicks like the haunting images in the verses, letting an in-joke be an in-joke. But if you listen to Prine for pleasure rather than to find songs for Bette Midler to cover, Rough establishes his ramshackle charm at its most casual and cult-deserving.

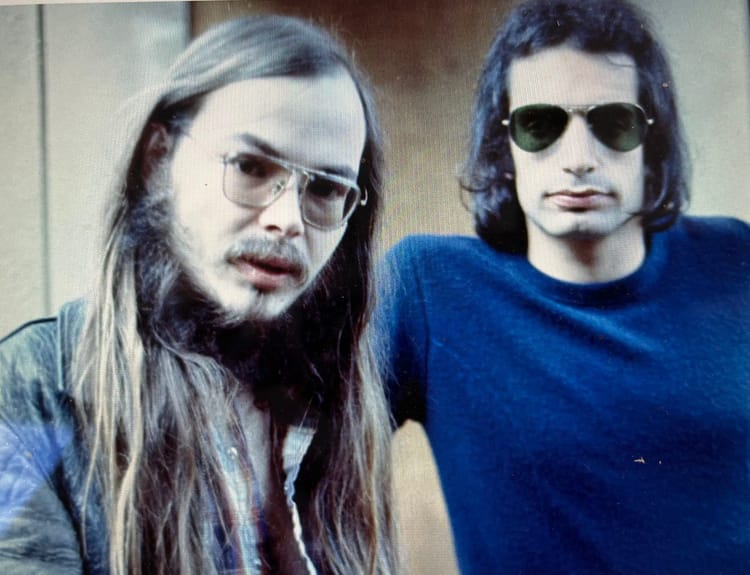

John Prine, avoiding the razor and paying tribute to "Dear Abby."

The modest, clean-faced kid of the first two albums is replaced by a bearded smoker in sunglasses and cowboy boots on Sweet Revenge, which delivers on that swagger. Granted, Prine is still a goofball who proudly reads “Dear Abby” and rhymes “I don’t wanna see ya” with “onomatopoeia” on a song full of the latter. But the title track (with back-up shouts from Cissy Houston!) is one of several tracks referencing jailbirds, “Often Is A Word I Seldom Use” has a honkytonk guitar hook over horns, and a chorus that ends with “[Grandpa] voted for Eisenhower cuz Lincoln won the war” comes off more bad-ass than any concurrent southern pride on the radio. Revenge might be the closest Prine came to being a shitkicker, or at least a crapkicker.

Fun fact! Prine’s first three albums - even Diamonds In The Rough! - were produced by “Atlantic sound” co-creator Arif Mardin, a little before he’d help the Bee Gees find their falsetto payday. Somehow, Mardin’s early ‘70s work with freaks like Prine, Goodman and Doug Sahm is regularly forgotten among the Aretha Franklin, Chaka Khan and Norah Jones credits. I wonder why.

"Fish And Whistle," so much better without pennywhistles.

Common Sense, produced by Steve Cropper instead of Mardin, is sprightlier musically but sour and insular lyrically compared to Sweet Revenge. The closing Chuck Berry cover is more fun than the Merle Travis cover last time, but “Come Back To Us Barbara Lewis Hare Krishna Beauregard” was less likely a crowdpleaser than “Dear Abby.” Four albums and zero hits in, critics and Atlantic Records were becoming less bullish on this New Dylan. Buoyed by a surprise SNL appearance (thanks to John Belushi, yet another Chicago icon in his corner), Prine left for Asylum Records, home to The Eagles, Linda Ronstandt, and numerous songwriters, like Prine, whom Ronstadt could plausibly cover. Prime Prine, a solid compilation of cuts from his first four albums, is recommended if you refuse to buy four good John Prine albums.

Maybe it’s just my dislike of pennywhistles, but the music on Bruised Orange is excruciatingly cute, as if Prine was a cuddlier Dylan who only needed a cuddlier Band behind him to get big, one that would respond to his couplets with carefree guitar licks, organ fills and hand claps. The professional boisterousness is indifferent to meaning and regularly overwhelms the singer. Leaning into the issue, Pink Cadillac (produced with the family Phillips at Sun Studios) is a retro rock & roll effort where Prine doesn’t care if you can tell what he’s saying, and half the songs are covers anyway. It’s not unpleasant, but criminally okay and unmemorable compared to his best work, lacking the personality NRBQ or Dave Edmunds’ Rockpile gave to similar efforts at the time.

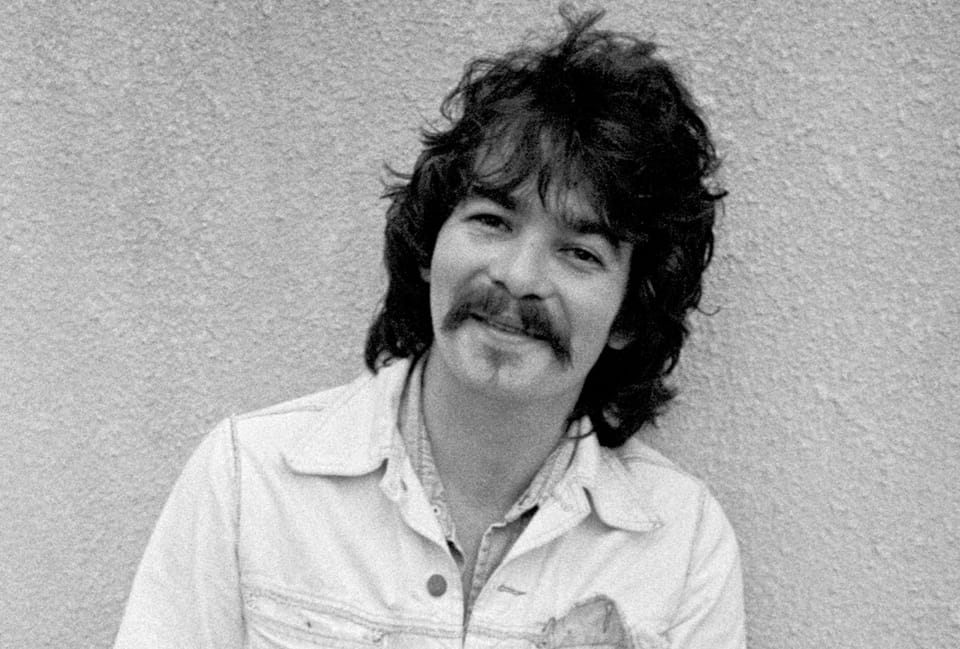

John Prine playing a low-slung electric guitar in 1980 just looks weird today.

The arrangements on Storm Windows are almost as generic as those on Bruised Orange, but with Prine front-and-center, making the vibe more Nashville product instead of a half-baked Planet Waves. Songs like “All Night Blue” and “Just Wanna Be With You,” obvious right from the title, show just how artful and spirited a straightforward Prine can be. Having found success and acceptance in the Nashville song factory, there’s an alternate reality where Windows was the new normal, setting up Prine as another respected industry name with a cult crowd like Rodney Crowell or JD Souther. But everybody who wasn’t an Eagle or Linda Ronstadt was skedaddling from Asylum by 1980, and Prine loathed rushing to sign with another label that would treat him as an afterthought. What happened next? Find out in Part 2!

John Prine and Diamonds In The Rough are at 162 and 169 on my Top 300 Albums of All Time, though expect the debut to be a lot higher next time. I'm telling you this because I've found people are more inclined to discuss and share reviews if there's a quantitative element at the top or bottom they can easily debate. Prove me right! Direct correspondence can be shipped off to anthonyisright at gmail dot com.